From Wood Chips and Mushroom Extracts to Vintner Coalitions: Government Funded Ecosystem Restoration Projects Enhance Vineyard Resilience

Chris Ott, former Environment Director of the Dry Creek Rancheria, recently told an audience of wine industry professionals how Russian River community growers, Jackson Family Wines, and the Dry Creek Rancheria Pomo tribe worked together to leverage millions in government grants from conservation agencies to overcome the twin climate challenges of wildfire and drought and build ecosystem resilience.

Speaking at the RISE Climate & Wine Symposium in St. Helena on April 6, Ott said that regional vintner groups across the state can leverage the same resources to get research and restoration grants. “The government is pushing out billions of dollars to support these efforts. I encourage everybody to be looking at these things, forming partnerships and establishing a community that can go implement these types of projects. In addition to that, the private funding world is coming around and there are funds available–because there’s a strong business case for these things.”

His presentation encompassed wildfire recovery and river restoration projects completed or underway in northern Sonoma County.

Wildfire Recovery and Resilience

When the 2019 Kincaid fire came through the Dry Creek Rancheria of the Pomo tribe on the east side of Dry Creek Valley, the fire and heat severely damaged the vegetation. Approximately 52 acres of lands burned, just as the rainy season was approaching.

“We had soils that were completely exposed,” Ott said. “What do you do?…we went into emergency mode. The tribe put organic fertilizer out to work with our native grass seeds that we planted and added in ryegrass to stabilize that soil…we also put straw down to cover it, and help keep the impact of rain from eroding the whole surface. The ground was sterile at this point.”

But over time, experts noted, the heat damaged land still had a lot of standing fuel, which had less moisture and was “therefore more likely to burn. Invasive species had also taken advantage of the newly created space and had started to colonize much of the former oak woodland, which created more fuel,” according to grant documents.

“A great number of you face the same situation,” Ott said.

The damage and the danger led the tribe to seek solutions with the help of professional experts.

“We had fire experts and land experts go and walk the site afterwards. We determined that there was at least three years of hand crew work that was required to mitigate the fuel load. So what do we do about it?

“We looked at it as an opportunity. Why? It’s an opportunity to recreate a healthy forest.”

That led to a surprisingly basic question. “Does anybody know what a healthy forest is?” he said. “And there were no answers.”

“We said, ‘okay, where does it start?’ And it starts with the soil.”

Wood Chip Treatment Enhances Soil Health and Native Species

With government funding,[1] [CO2] the tribe launched a research program with test plots to determine the impact of various practices in bringing back soil health and vegetation balance. The project compared the soil and vegetation health using the conventional approach–small burn piles with another that used a wood chipper on site. The team then applied mushroom extracts to the chips to accelerate decomposition.

There were challenges. One was that there “were a lot of naysayers out there saying that’s [the wood chipper approach] impossible,” Ott said. “‘It will not work. You will never get anything to grow.’ The other thing that we were told was that ‘you can’t get a chipper up on the hillside.’ If you see that terrain, it’s pretty steep. But the track wood chipper walked right up the hill. No problems.” He noted that there were “certain limitations and things that we want to make sure that we were not impacting the forest floors, but it’s totally do-able.”

The point of this was taking a risk management approach to land stewardship. We were not out to reduce the fuel. And as we started to think about it, we started to see that taking that carbon and putting it back into soil is the best solution.

The decomposed wood chips removed fuel by returning biomass to the soil. This approach brought back native species, while the burn pile test plots let invasives return more quickly and crowd out natives. In addition, the researchers found that the moisture content in the chipped plots had twice the moisture of the burn pile test plot.

Another unique aspect of the projects: tribal elders advised on incorporating Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK).

Ott said that after the forest soil restoration was underway, elders advised him to cut down half of the oaks, saying the density was more than what it should be to have healthy oak forest. They relayed historic cultural learnings on what the density was like in previous decades.

“When I started working with tribal elders, and going back in time, and looking at the 5,000 years plus traditions of highly managed and manipulated forests by Native Americans, what we found is a forest completely different than what they are today.”

“The First Nations actually farmed the forest, especially in the Sonoma area and areas where there are oak woodlands, because those acorns were part of their sustenance. It was a crop that they harvested. They used fire as one of the many tools, but fire was really never used to reduce fuel. As was described to me, oak trees had 100 foot canopies. So if you can imagine a forest with oak trees and 100 foot canopies…That’s what oak forests are supposed to look like.”

Ott said that while soil is important, the fire resilience soil health project dovetailed with water quality.

“We did the forest management projects to improve water quality,” he said. “While our goal was to make sure that we restored culturally important salmon habitat for the tribe, , we did forest and land stewardship for water quality–the result was water quality improved and we had twice as much moisture in the ground feeding the streams. That is good for the environment and a good business proposition to have more water available for agribusiness. When you are looking at the bottom line, all of these things make economic sense, and it starts with there is no such thing as a waste. We must harvest every opportunity that we can including turning fuel load into carbon for the soil.”

Creek and River Restoration: Initiatives Expand to Encompass Broader Regional Watershed, Growers, and Community

The tribe was also concerned about restoring health to an unnamed creek running through Tribal land and the Russian River in order to restore salmon habitat.

Here projects began to blossom into area wide efforts, involving major landowners, including Jackson Family Wines, and other growers, along with the tribe, creating a watershed enhancement and management project and the Alexander Valley Flood-Managed Aquifer Recharge, or “Flood-MAR.”

Invasive Weed Removal Furthers River Health

In this series of projects, the Tribe has removed stands of invasive, water hogging, wild reed, Arundo donax. Arundo displaces native plants and fish, is also flammable and spreads fire along waterways, according to UCANR experts.

The project has enjoyed widespread participation, including funding from the North Coast Resource Partnership.

Ott said the project was the first to remove Arundo from the main stem of the Russian River where the plant didn’t grow back right away. “Anybody knows that this plant is a terrible, horrible plant.” he said. “We removed that from the watershed, saving over 60 million gallons a year of water. And that Arundo has been eradicated. It’s been three years and hasn’t come back. So I’m happy about that.”

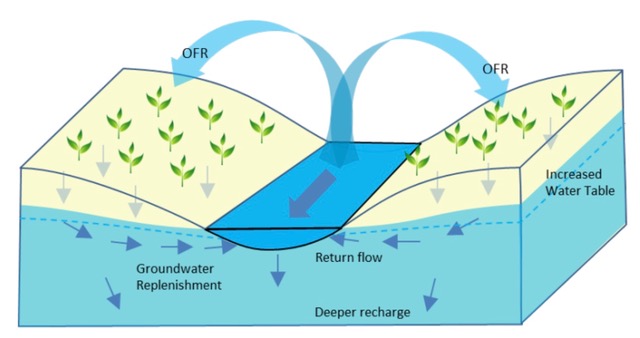

Groundwater Recharge: Vintners Support Alexander Valley-MAR

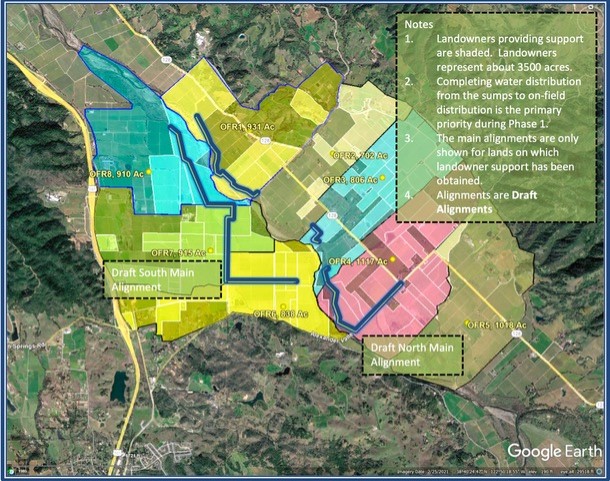

A broad coalition of area vintners is supporting the “Flood-MAR” groundwater recharge project which has received $7 million from the Department of Water Resources out of the requested $9.6 million in grants. The project encompasses 7,000 acres of vineyards. Dry Creek Rancheria, who are also growers (with 150 acres of vineyards), is administering the program.

Participating wineries include Jackson Family Wines, Constellation Brands, Foley Family Wines, Rodney Strong, Vino Farms, Silverado and Robert Young. (Wineries do not receive any grant monies from the project, but do receive environmental benefits the project is designed to provide.)

Ott said the first groundwater recharge flows were anticipated to begin in 2024.

Additional support is provided by the North Bay Water District, National Marine Fisheries Service, Sonoma Alliance for Viticulture and the Environment, Sonoma County Farm Bureau, Trout Unlimited, North Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board, Sonoma Water and the County of Sonoma.

In a followup interview, Ott said the project takes water from the river only when required high flow thresholds are met, and then pumps the water upland to growers. The goal is to “start saturating the ground,” he said, “slowing the water down, too, so the base flows of the river will increase over time.”

Ott said the project also offsets the effects of hardened surfaces–paved roads and other development –that have decreased water absorption over time. It is hoped that the recharge project will begin to compensate for that.

When it comes to groundwater recharge and water conservation, Ott made the case that this is a no brainer.

“It only makes sense to protect your core business, especially in the wine, business, and agriculture as a whole. It makes absolute sense to be involved in groundwater recharge projects…those days of believing and trying to convince investors to invest in these programs are over. There’s a whole group out there that is solely investing in these kinds of projects.”

Government Funding and Private Support for Resilience Is Growing

Asked if these kinds of regional grant funded programs were a good model for other vintners who want to reduce fire and drought risks, Ott was emphatically optimistic: the time is right for vintners to embark on similar projects.

“When I started in this business…there were lots of obstacles to taking a holistic or systemic approach to ecology and climate change. All of us were struggling through those days… there was no political will to do that…things have changed now.

“The missing element layer earlier was community…It takes community action now. And there’s a business case for this…there’s a political will to do it. There’s a necessity to do it. And all of the technologies are available somewhere in the world. So the biggest changes that I’ve seen are just that ‘now is the time.’”

Ott also offered a hot tip for new grant funding opportunities growers should look into.

“Hopefully some of you are aware that the State of California has a new biodiversity initiative [https://www.californiabiodiversityinitiative.org/] called 30 by 30, where they want 30% of the area to be protected by 2030. And I think they’re taking a pretty broad view of incorporating public and private lands together and how the funding will be allocated… I think many groups should be looking at how to access new sources of funds for biodiversity in particular.”

Making the commitment to third party certification takes time and effort, but it is worth it to demonstrate our commitment to the community and to protect our watershed, our land and the air we breathe.

- Susan Boswell, Chateau Boswell Winery