Speaking at Napa Green’s Napa Rise climate action workshop on energy on April 5, 2023, Jay Famiglietti, global futures professor in the Arizona State University School of Sustainability and former senior water scientist at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), told the audience of wine industry professionals that California needs to take more aggressive steps to preserve the state’s water and energy resources.

“We passed — overwhelmingly passed — Prop 1 in 2014 to develop new water storage in the state, and still nothing’s been built,” he said. “The science is all there, the graphs are all there. We know what’s happening. But people aren’t changing. And that’s a real tough nut to crack.”

Water for Agriculture

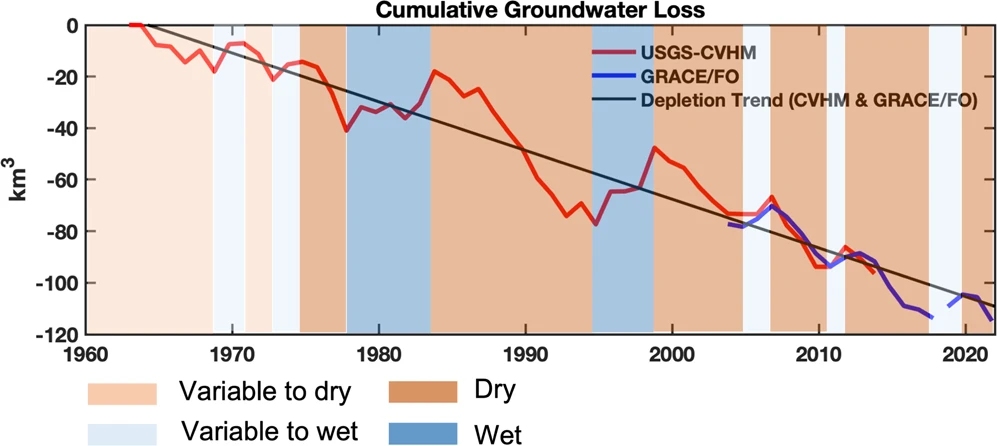

Best known for his pioneering use of satellites at JPL to monitor groundwater depletion, primarily in Central Valley aquifers, Famiglietti’s most recent research, “Groundwater depletion in Central Valley accelerates during megadrought” published in Nature Communications, found that the groundwater depletion is accelerating significantly; he’s documented a 31% higher rate of groundwater depletion since 2019 in two years of California’s drought.

“Groundwater supplies roughly two-thirds of California’s water supply during droughts, compared to one-third in non-drought conditions,” Famiglietti and his colleagues wrote in their 2022 paper. Furthermore, he confirmed estimates that the state expends 20% to 25% of its energy use moving water around the state, showing how the two resources are inextricably linked in California’s economy.

In his talk, he reiterated to the St. Helena, Calif., audience the oft quoted statistic that agriculture uses 80% of the state’s water, with nut trees comprising one-fifth of total ag water use. “I question how many almonds and pistachios the world needs,” he said.

Though winegrapes use roughly 40% of what nut trees use, water is still a significant concern for wine growers. (According to Department of Water Resources statistics, quoted by the Pacific Institute, grapes use about 1.6 feet of water, while almonds and pistachios require an average of 4.0 feet.) And while some wineries are making progress in their efforts to reduce water and energy used in the winemaking process, experts on the panel quoted statistics that, in the wine industry, 95% of water use takes place in the vineyard and only 5% in the winery.

Water Challenges

Droughts, combined with atmospheric rivers and subsequent flooding, are working in tandem to worsen the extremes, Famiglietti said.

“We know that the water cycle is changing rapidly…we know we’re in the middle of this whiplash scenario such as we’ve experienced here in California, from the throes of the driest situation ever to this incredibly wet winter that we’ve just had. We also have sea level rise, and we’re battling coastal inundation and coastal erosion.

“We need to use water right to thrive on this planet and to do all the things that we want to do — grow food and use water for the environment and for humans, water to produce energy and water for economic growth,” he said. “It takes a tremendous amount of water to produce energy, and it takes a tremendous amount of energy to heat and treat and transport water. And of course, we need an awful lot of water and energy to grow food. So these are all intimately linked, and we should be thinking about them holistically.”

Groundwater Depletion

Groundwater depletion, Famiglietti said, “is happening in most of the world’s major aquifers right now, and it’s super important here in California during drought periods. During certain periods, we can be using almost 100% groundwater toward the end of a long phase of drought.”

Chart: Groundwater depletion in California’s Central Valley accelerates during megadrought.

Showing graphs comparing USGS and satellite data, he said, “you can see the huge increase in flooding and increase in drought just over the last six or seven years. We need to see what we can do to stop those depletion trends to keep California from going deeper and deeper into the red.

“The challenge in much of California is the fact that we’ve got this episodic and uncertain delivery of rainfall through the atmospheric rivers,” he continued. “And yet, we need water all the time. The challenge is to actually try to figure out how to increase the storage. We’re probably not going to be building reservoirs, right? So how are we going to be effecting managed aquifer recharge?”

Critical of the state Sustainable Groundwater Management Act’s approach to localizing water decision making by having individual water districts submit required plans, he instead called for statewide, science-based targets. “I think I think that’s the future. We need to give a lot of attention to the storage issue, and how do we balance?” he said.

“I think the state needs to be better prepared to figure out how to do these things,” Famiglietti concluded. “Where are the opportunities? Where are the locations for recharge? How much can we do? Where do we do it? Are the fields in good enough shape? Do they have too many fertilizers that are just gonna end up contaminating the groundwater? These are all things that need our attention, actively.”