From Merlot’s flavor to Cabernet’s acidity, here’s how climate change is reshaping the world’s most beloved wine regions

“We pulled up about three acres of Merlot, which sounds probably crazy,” says Heelan. She explains that the winery is planting new varieties better equipped to tolerate the hotter weather that’s becoming commonplace. “It’s really about the future and the pursuit of understanding and experimentation.”

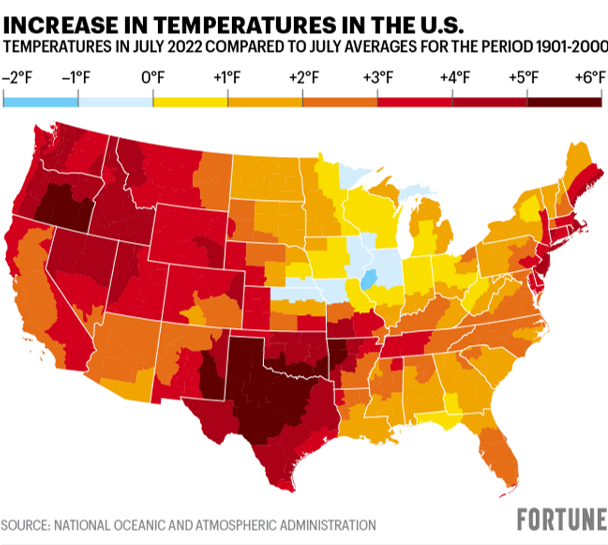

Winemakers in regions that produce some of the world’s best-loved wines—like California’s Napa Valley, and France’s famous Rhône Valley—have been badly hit by climate change in recent years. Now, wineries are taking measures to protect the future of their precious vines.

In drought-stricken California, winemakers are experimenting with dry farming and wastewater recycling in addition to growing new varieties. In France, as winemakers recover from what French Agriculture Minister Julien Denormandie called “the greatest agricultural catastrophe of the beginning of the 21st century,” the Côtes du Rhône and Côtes du Rhône Villages AOCs are unveiling new sustainability pledges.

But even as winemakers adapt, many consumers are unaware of the changes afoot or what makes for sustainable practices in the industry.

Beyond the steps taken to cope with climate change, marketing challenges may also lie ahead for wineries, and some advocates of sustainable wine say consumer buy-in is imperative to broader action.

New flavor profiles

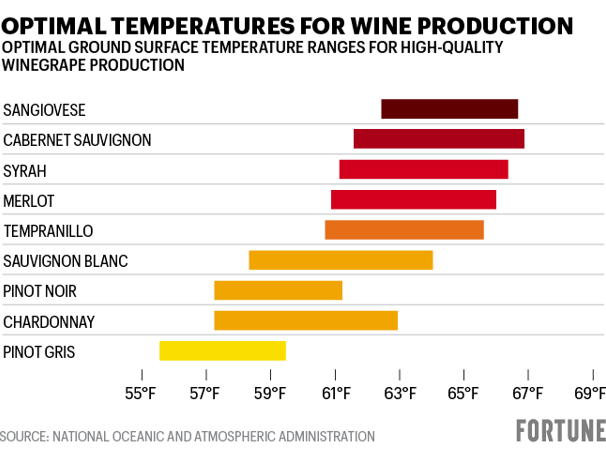

Larkmead is a Cabernet house, but the changing climate could mean faster ripening fruit and different tasting wines. As daytime highs increase, Heelan hopes that blending her newly planted grape varieties with Cabernet will allow the winery to continue making the wine it is known for, without sacrificing flavor or style.

“We plan to stay a Cabernet house,” she says. “But Cabernet might lack a little bit of acid in the future.”

Heelan might be ahead of the curve when it comes to adapting to changing weather patterns.

“Being at this specific location, we are just seeing the effects of climate change before other people in the valley,” Heelan says, explaining that her region of Napa doesn’t benefit from the fog layer that helps cool vineyards further south. “I do think that five years, 10 years from now, they’re probably going to have less of that maritime influence as the climate changes.”

Not all wineries are ready to take the plunge with experimental vines just yet.

“I don’t know if Napa [has] fully come to terms with just how much they may need to shift some of the grape varieties in the future,” says Anna Brittain, executive director of Napa Green, a certification program for sustainable wine growing whose focus includes climate action and regenerative farming. She advises growers on how to improve soil health, water retention, and biodiversity to increase vine resilience in the face of drought and high heat.

Dry-farming methods

In California, the water year that ran from October 2020 to September 2021, was the driest in nearly a century. And wineries that have started investing in water efficiency practices are already seeing the payoff. The 55-year-old Chappellet Winery installed a more efficient water treatment facility in 2011.

“One hundred percent of our winery’s process water is pumped and purified for use in the vineyard,” says president and CEO Cyril Chappellet. “On a full-production year, we estimate that close to three acre-feet of treated water is returned to our irrigation reservoir for vineyard irrigation, which is just under 1 million gallons.”

Other wineries are trying to adapt with dry farming, a method that requires minimal irrigation. The soil is prepared after each harvest to allow it to efficiently capture rainfall.

Five years ago, Hamel Family Wines began trialing dry-farming practices at three estate vineyards. Winemaker John Hamel said he learned about the approach in France, where a prominent winegrower suggested that irrigation disconnects the plant from its terroir.

It has the added benefit of allowing the winery to operate with 2 million fewer gallons of water each season. Last year, despite the historically low rainfall, the winery was able to dry-farm 75% of its vineyards.

Across the Atlantic, French winemakers have climate-related problems of their own. In 2021, a late frost damaged young buds, resulting in catastrophic crop losses.

“Winegrowers remain quite helpless to face the power of climatic events,” says Philippe Pellaton, president of Inter Rhône. He says there are a few exogenous solutions to protect the vines against frost, such as heaters or candles. “These are palliatives that can be implemented only on high-value plots but not on the entire vineyard.”

Inter Rhône, which represents the Rhône Valley vineyard AOCs, recently shared news about sustainability pledges that seek to address the challenges ahead. The pledges include ensuring the transparency of practices; protecting biodiversity in the Côtes du Rhône vineyards; respecting terroir while preserving resources; and working toward passing on a legacy by protecting the vineyards for future generations.

‘Heads in the sand’

According to Brittain, winemakers’ reactions to shifting weather patterns remain diverse.

“I think it hugely varies, from people that still have their heads in the sand, to people that are absolutely panicked,” she says, adding that many consumers don’t truly understand what it means be a sustainable wine. “There’s a real chasm there in consumer understanding, I think, between ‘organic’ and sustainability.”

Just as shifting practices is tough, so is communicating the value of the change and any additional costs to consumers.

Brittain is confident that more producers will invest in sustainable practices if they see that customers are willing to pay a premium. But as New York–based sommelier Carrie Lyn Strong points out, it’s hard for customer-facing wine industry professionals to tell this story succinctly to their customers, particularly as it isn’t a light topic.

“You have to have people really care about it in a way that makes them pay attention,” she says.

Despite such challenges, it’s clear to many winemakers that the time for inaction is over. Even as Heelan looks forward to harvesting the new varieties in 2024, she says she wishes she had acted sooner.

“Hindsight is 20/20,” she says. “I wish we planted it 10 years ago.”

This story is part of The Path to Zero, a special series exploring how business can lead the fight against climate change.

Making the commitment to third party certification takes time and effort, but it is worth it to demonstrate our commitment to the community and to protect our watershed, our land and the air we breathe.

- Susan Boswell, Chateau Boswell Winery